Your guide to common typography terms

You’re surrounded by written words everyday but probably don’t think twice about how their design impacts your perception. What if I told you that typography, which is the art of arranging letters and characters, could influence your impression of truth? In 2013, the film maker and author Errol Morris ran a test in the New York Times to determine if a statement written in one typeface would be judged as more truthful than another. The answer? Readers found that when the statement was written in Baskerville it was statistically more believable than the alternatives.

In this blog post I am going walk you through a few typography terms, clarifying common misunderstandings, and try to help you gain an appreciation for the impact of type design.

A Font Is Not a Typeface

Although font and typeface are sometimes used interchangeably, there is a distinction. Times New Roman is a typeface and it encompasses variations such as Times New Roman Bold and Times New Roman Italic, which are both fonts. Technically then, 12-point Times New Roman Bold is one font variation of the typeface Times New Roman.

While the term typeface is used to describe an entire type family, fonts are digital files that contain a specific version of a single typeface. To get the full picture of the particulars of a design’s layout you need to know which typeface is being used and in what size and weight (the font). If you ask a designer which font she chose to use on a project, she won’t just answer Times New Roman or Helvetica (assuming she’s a stickler for terminology) because those are typefaces.

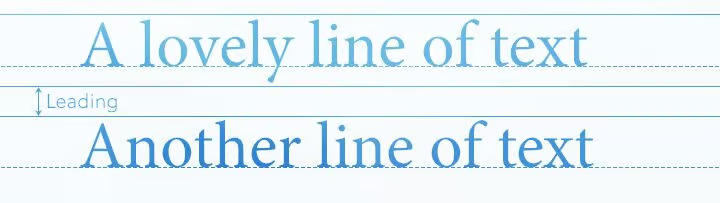

Leading and Line-spacing

Line spacing is the vertical distance between lines of text, measured from baseline to baseline.

The traditional term for line-spacing is leading (rhymes with “bedding”), but in interactive design line-spacing is the more common term. The term leading comes from the days when typesetters had to set individual letters by hand and used lead strips to separate lines of text and increase vertical spacing.

Most people probably think of line-spacing in terms of single-spaced and double-spaced, which is a convention left over from the days of typewriters. The carriage on a typewriter can only move in whole line space units (e.g. single or double rather than 1.2 or 1.5) and the convention stuck around. As a blossoming type-snob I hope you’ll agree that neither single nor double-spacing will do. While single-spacing is too dense an option for body copy, double-spacing – although the default for college papers everywhere – is actually too loose for easy reading.

There’s no magic formula, but the sweet spot for most text is to make the line-spacing around 120% to 145% of the font’s size.

Why does it matter? Outside of font size and weight, the line-spacing of text is one of the key factors in determining its readability.

Measure

Measure, sometimes called line length, is defined as the horizontal length of a line of type on a page, and is one of the easiest type rules to follow.

The classic ideal for single column printed text is 66-character lines (counting both letters and spaces), however on mobile devices and the web 80 to 100-character line columns are routine and not considered type sin. This blog’s line length is around 68 characters on my laptop, meaning it’s not so long that my neck swivels from side to side as I read and not so short that my eyes start to feel like pinballs jumping back and forth. When designing a new type system I sometimes copy and paste lines into a character counter to fine tune column lengths.

Kerning

Kerning is the process of adjusting the horizontal space between individual, consecutive letter pairs. Kerning is sometimes confused for tracking. Both refer to the amount of space between characters of type. Tracking is more general and affects the uniform spacing between all characters in a range of text. You might fine-tune the kerning between two letters in a logo or a headline but you would adjust the spacing of an entire page with tracking.

Well-kerned words are visually pleasing, balanced, and don’t leave any confusion as to where a word ends and begins.

Should you ever find yourself stuck trying to nudge individual letters into just the right place, try any of the fancy tricks that professional designers use: you can look at a word upside down, you can print the word out and look at the paper from directly above or below, or you can blur your eyes – anything to help you focus on the spacing.

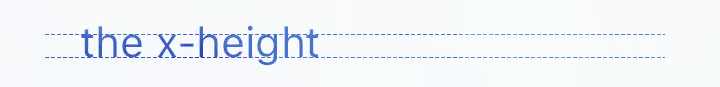

X-height

X-height is typically the height of the lowercase letter x in a font. Technically, it’s the distance between the baseline of a line of text and the tops of the body of the lower case letters.

Why does it matter? X-height isn’t a huge concern until you start dealing with fonts at small point sizes – like on mobile devices – and then it can make a huge difference in whether text is legible. The taller a font’s x-height, the more clearly its letters are defined.

A notable feature of Apple’s newly designed typeface, San Francisco, is its large x-height. This helped to improve legibility at small sizes, and made it a better option for the Apple Watch’s scale.

Other resources:

Practice your kerning skills: http://type.method.ac/

The typographic dating game: http://www.typeconnection.com/